4 Notes on Seeing a Mature(!) American Chestnut Tree

The American Chestnut once dominated eastern forests – an apex species that shaped both the Eastern Woodlands landscape and human communities. Then, in barely three decades from 1904 onwards, a blight imported from Asia wiped out billions of trees.

Their seeds are still in the ground and occasionally if you’re hiking deep in the forest you can see a baby American chestnut coming up out of the ground, but they’re always just quickly killed off by the blight. What’s exciting though is that the scientists at SUNY-ESF Darling 58 have used genetic engineering to splice in a few variants of the American chestnut that are resistant to blight, and they have been planted at test sites all around the Eastern seaboard. I got to see one at the Lake Allatoona Dam near Cartersville, Georgia.

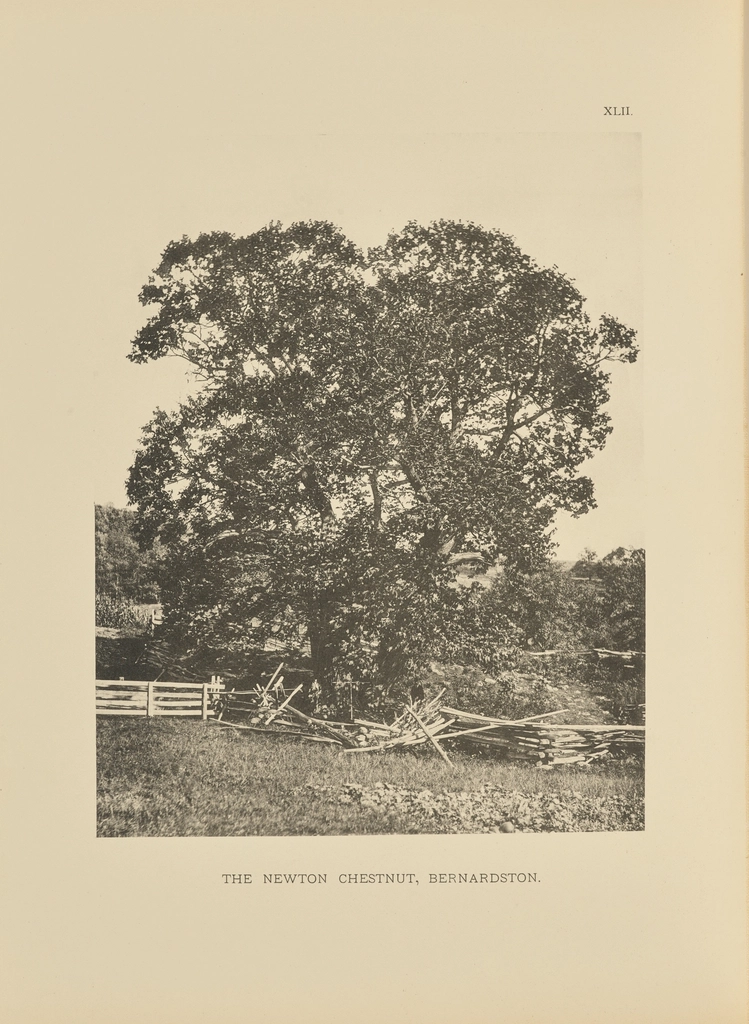

They are huge, robust, and beautiful

I can definitely see how they ruled the forest for years and why their wood was so valuable to early white settlers and to Indigenous Americans.

The American chestnut, Castanea dentata, once dominated portions of the eastern US forests. (View the American chestnut range map.) Numbering nearly four billion, the tree was among the largest, tallest, and fastest-growing in these forests. For thousands of years, the original inhabitants of the Appalachians coexisted with the American chestnut. (Read Indigenous Words for Chestnut.) The nuts provided an abundant food source, and Indigenous Peoples responded in kind by managing the landscape to improve habitat for chestnuts. Humans benefitted not only from the chestnuts themselves, but from the immense opportunities it created for wildlife.

Chestnuts are dense with calories, rich in vitamin C and antioxidants, and the leaves contain higher levels of essential plant nutrients than other local tree species. This made the chestnut beneficial not only for the humans of an ecosystem, but for every level of the food chain. Chestnut leaves were favorites of detritivore insects who, by breaking them down, enriched the forest floor with nutrients. Insects feeding on chestnut leaves were then eaten by fish or birds, and other larger animals would feed directly on the chestnut mast like squirrels, deer, bear, and turkeys.

The chestnuts will really get you

I had no idea that the chestnuts were that big and that hard and that prickly. Like they’re like a weapon almost. And I can see why you would really need to roast them and why they can be such valuable food if you know how to get past the covering.

The leaves are distinctive

When we toured the dam area, I did not know that there were American chestnuts planted on the Army Corps of Engineers land. But when I saw them, the leaves are so shaped differently and distinctive that it was quite obvious that this was not a hickory, it was not an oak, it was definitely. Definitely something different, and which led me to look up that it was an American chestnut.

This project is so exciting

I’m a bit of a nerd for bringing back trees. I actually planted a Princeton American Elm in my backyard, which was another species that’s been killed off by disease and is slowly making a comeback. It’s exciting for a native species that was wiped out by human activity so quickly to be able to be brought back by human activities.

I’m so hopeful that the project will not only be successful to bring back the American chestnut but also show a path that we can use to protect and restore. Trees like the Eastern Hemlock and the Ash, and so many of our majestic North American species that are just getting hit hard by the forces of globalization and human activity.

I highly recommend seeking out a planting site. They are surprisingly easy to find and scattered all up and down the eastern seaboard.